Childcare from the Perspective of Women Informal Workers

Извор: WUNRN – 09.11.2018

Rachel Moussié, Deputy Director, Social Protection Programme, Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO), Paris, France

Women informal workers across the world have set out their demands for quality public childcare services through a campaign organised by the research-action-policy network WIEGO (Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing). The campaign grew out of research in five cities – Belo Horizonte, Brazil; Accra, Ghana; Ahmedabad, India; Durban, South Africa; and Bangkok, Thailand – in which interviews with women in informal worker organisations revealed the extent of the need for quality public childcare services (Alfers, 2016).

Informal employment accounts for more than half of non-agricultural employment in the global South, and more women than men work informally in South Asia (83%), sub-Saharan Africa (74%) and Latin America (54%) (Vanek et al., 2014). Given the size of the informal economy, our approach at WIEGO is to start from the perspective of informal workers and the daily struggles they face to earn a livelihood. Workers want to secure a better future for their children but their long working hours, low earnings and poor working conditions make it difficult to find the time and resources to care for them. As informal workers, most do not receive any maternity protections and are obliged to earn an income even though their infants may be only a few weeks old. In focusing on women informal workers, we are also reaching some of the most marginalised children in urban areas.

Our research explored the childcare arrangements of 159 women informal workers including home-based workers, domestic workers, street vendors and market traders, and waste pickers in the five cities. They all had children under the age of 7 in their care; 82.5% were mothers, 15% were grandmothers and 2.5% were aunts. The type of childcare arrangement chosen depended on the institutional framework governing childcare in each country; social and cultural norms; and differences between individual workers – for example, income levels – and between groups of workers.

In Belo Horizonte, for example, the waste pickers interviewed rely on the public childcare service; however, in Durban and Accra, traders use informal and unregulated childcare services or bring their children with them to the markets if childcare centres are too expensive or of poor quality. Bringing children to work in crowded urban spaces can be dangerous for children’s health and development and is distracting for workers, who see their earnings drop. In Ahmedabad, workers who are members of the Self Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) benefit from the childcare cooperative that is adapted to their working hours, providing nutritious food, education and healthcare (Moussié, 2017).

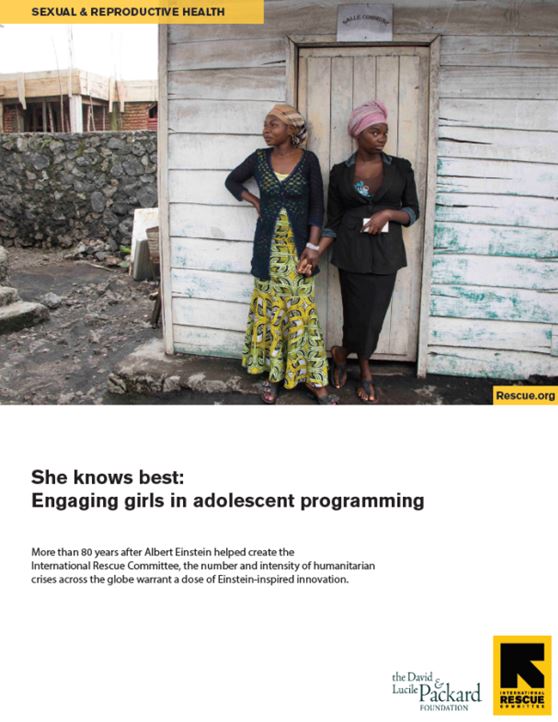

Photo: Paula Bronstein/Getty Images Reportage

The research dispelled the myth that women informal workers can always depend on relatives to care for their young children while they work. Women informal workers are reluctant to leave their children in the care of relatives or neighbours because they worry about their children’s safety in overcrowded cities and the lack of stimulation and care they receive. They are also expected to make cash or in-kind payments to those who look after their children. WIEGO research shows that to achieve positive early childhood development outcomes, the needs of the children and the women informal workers caring for them must be considered.