A Double Pandemic: Domestic Violence in the Age of COVID-19

Извор: WUNRN – 16.05.2020

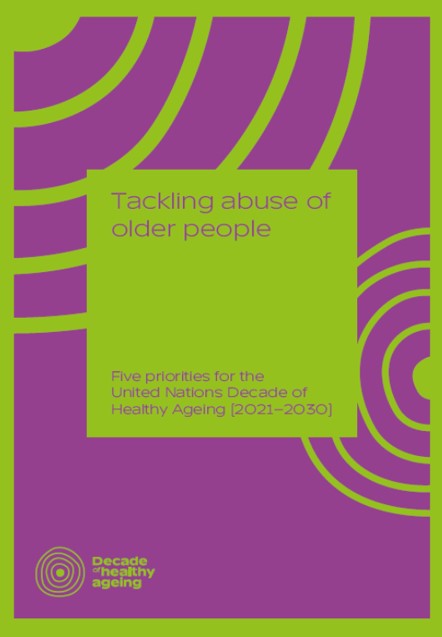

People look out of their apartment windows to show gratitude to health-care workers during the coronavirus outbreak in Madrid, Spain. Susana Vera/Reuters

By Caroline Bettinger-Lopez, CFR Expert & Alexandra Bro – May 13, 2020

Governments worldwide have imposed lockdowns to contain the coronavirus, but those same restrictions have increased the risks associated with domestic violence, especially for women, children, and LGBTQ+ individuals.

Around the globe, governments have implored residents to stay home to protect themselves and others from the new coronavirus disease, COVID-19. But for domestic violence victims—the vast majority of whom are women, children, and LGBTQ+ individuals—home is a dangerous place.

How have lockdowns influenced rates of domestic violence?

Data from many regions already suggests significant increases in domestic violence cases, particularly among marginalized populations. Take for example the Middle East and North Africa, which have the world’s fewest laws protecting women from domestic violence. An analysis by UN Women [PDF] of the gendered impacts of COVID-19 in the Palestinian territories found an increase in gender-based violence, and warned that the pandemic [PDF] will likely disproportionately affect women, exacerbate preexisting gendered risks and vulnerabilities, and widen inequalities. In Latin American countries such as Mexico and Brazil, a spike in calls to hotlines in the past two months suggests an increase in domestic abuse. Meanwhile, a drop in formal complaints in countries such as Chile and Bolivia is likely due to movement restrictions and the inability or hesitance of women to seek help or report through official channels, according to the United Nations and local prosecutors.

In China, police officers in the city of Jingzhou received three times as many domestic violence calls this past February as in the same time in 2019. Some high- and middle-income countries, such as Australia, France, Germany, South Africa, and the United States, have also reported significant increases in reports of domestic violence since the COVID-19 outbreak.

It’s important to remember that domestic violence was a global pandemic long before the COVID-19 outbreak. According to data collected by the United Nations [PDF], 243 million women and girls between the ages of fifteen and forty-nine worldwide were subjected to sexual or physical violence by an intimate partner in the last twelve months. Put a different way, one in three women [PDF] has experienced physical or sexual violence at some point in her life. LGBTQ+ individuals experience similarly high levels of violence.

People look out of their apartment windows to show gratitude to health-care workers during the coronavirus outbreak in Madrid, Spain. Susana Vera/Reuters

Today, rising numbers of sick people, growing unemployment, increased anxiety and financial stress, and a scarcity of community resources have set the stage for an exacerbated domestic violence crisis. Many victims find themselves isolated in violent homes, without access to resources or friend and family networks. Abusers could experience heightened financial pressures and stress, increase their consumption of alcohol or drugs, and purchase or hoard guns as an emergency measure. Experts have characterized an “invisible pandemic” of domestic violence during the COVID-19 crisis as a “ticking time bomb” or a “perfect storm.”

What has been the impact on social services for domestic violence victims?

Cities around the world have seen a dramatic increase in the demand for social services and assistance, especially from people in vulnerable conditions who may not legally qualify for social welfare. Meanwhile, social, health, and legal service providers—such as shelters, food banks, legal aid offices, childcare centers, health-care facilities, and rape crisis centers—are overwhelmed and understaffed. Some shelters are full; others have been converted into health facilities.

As prisons have become hotbeds for the spread of COVID-19, some criminal justice authorities are halting arrests and releasing inmates. These are critically important public health measures that should be accompanied by alternative means to prevent and interrupt domestic violence, such as individualized risk assessments, efforts to notify victims of pending inmate releases, and safety-planning support for victims. Unless governments provide sufficient guidance, resources, and training to local authorities, people will continue to be at greater risk of domestic violence.

What can countries do to protect those at risk of domestic violence amid the pandemic?

As the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and the United Nations have emphasized, countries must incorporate a gender perspective in their responses to the COVID-19 crisis. Several countries and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have already taken innovative steps in this direction. New campaigns also use social media to spread awareness of resources available to survivors, including hotlines, text message–based reporting, and mobile applications.

Social distancing has increased people’s reliance on technology and changed the way mental health, legal, and other social services are provided to survivors unable to leave their homes. With disruptions to the criminal justice system, countries have shifted to virtual court hearings, facilitated online methods for obtaining protection orders, and communicated their intentions to continue to provide legal protection to survivors.

Moving forward, it is critical that states support the development of alternative reporting mechanisms; expand shelter options; strengthen the capacity of the security and justice sectors; maintain vital sexual and reproductive health services, where domestic and sexual violence victims are often identified and supported; support independent women’s groups; finance economic security measures for women workers, especially those serving on the front lines of the pandemic or in the informal economy, and other groups disproportionately affected by the pandemic, such as migrant, refugee, homeless, and trans women; and collect comprehensive data on the gendered impact of COVID-19.

How is the pandemic likely to affect long-term progress toward ending domestic violence?

Elected officials and the general public are now more aware of this invisible pandemic than before, and the connection between physical insecurity and economic insecurity is suddenly more tangible for people who might otherwise have been less attuned to domestic violence. There is now a unique opportunity to shine light on the economic dimensions of domestic and gender-based violence, create financial safety valves for victims, and consider public health-oriented, non-carceral approaches that address prevention and root causes.

At the same time, this pandemic has the potential to continue to marginalize domestic violence survivors in dire need of support amid what could become the greatest global economic crisis in modern history. For survivors, particularly those who are marginalized or underserved, the pandemic could reinforce their mistrust in formal systems and alienate them further. Repairing those relationships would be an enormous challenge that would require an overhaul of conventional approaches to prevention, response, and treatment. Governments, NGOs, and the private sector need to incorporate a human rights and gender lens into all of their COVID-19 responses and funding structures to address this new reality.

https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/double-pandemic-domestic-violence-age-covid-19